The world has produced more than eighteen trillion pounds of plastic to date, and over eighteen billion pounds of plastic has trashed our planet.

It enters the ocean every year and ensnares marine animals we cherish — and much of the rest leaches toxic chemicals into the ground or sits in landfills, where it can take up to 1000 years to decompose.

The often-cited negative impact of using so much traditional plastic made from petroleum-based raw material has left manufacturers and consumers scrambling for an alternative to the ubiquitous material, and bioplastics have emerged as a potential solution to plastic pollution.

The name bioplastic sounds promising, with a prefix that hints at a “natural” product. But is bioplastic a flawless solution to our environmental issues?

The answer?

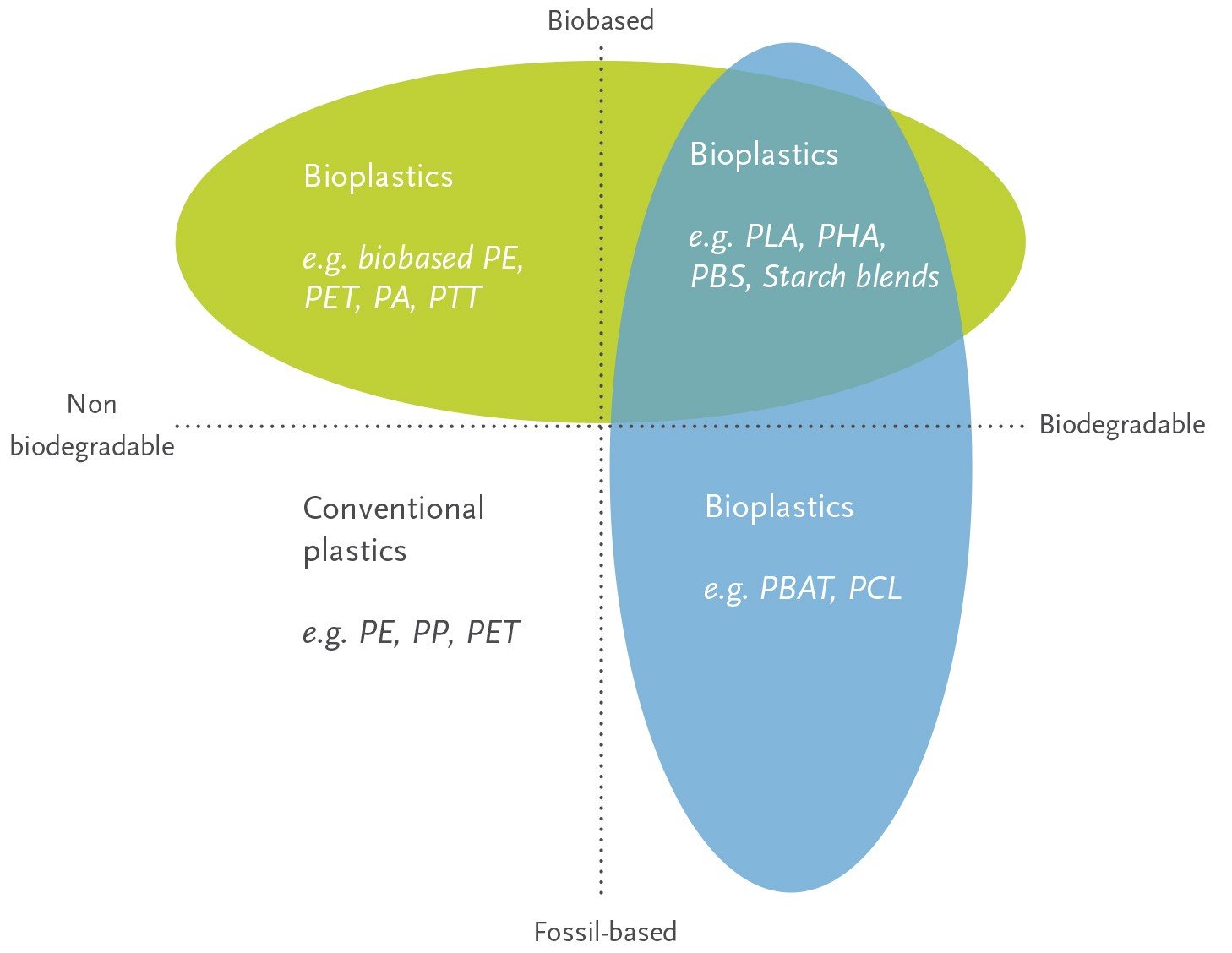

Contrary to what many would like to think, the use of “bio” does not necessarily mean that the finished product, plastic or otherwise, is earth-friendly and biodegradable.

Bioplastic is a confusing vague term, and it might have you think that a bioplastic wrapper will break down on your compost heap, or will at least have a lower carbon footprint. Surprisingly, neither is necessarily true.

So what is bioplastic?

Bioplastic simply refers to a plastic substance made (wholly or partly) from plant (biomass) or other biological materials rather than petroleum. It is also often referred to as biobased plastic.

It can either be made by extracting starch and cellulose from plants like corn and sugarcane to convert into polylactic acids (PLAs), or it can be made from polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) engineered from microorganisms.

PLA is one of the most popular bioplastic in the market today and is commonly used in food packaging and catering products, while PHA is often used in medical applications such as sutures, slings, bone plates and skin substitutes.

What happens when we’re done with bioplastics?

It’s worth noting that “biobased” does not equal “biodegradable”.

Therefore, not all bioplastics made from biomass are biodegradable and could still be in the same condition for years. Some additives such as antioxidants make biobased plastic degrade more quickly in nature.

Depending on the type of polymer used to make it, there are various ways we can discard biobased plastic waste.

Firstly, bio-based plastics such as PLA can be recycled through plastics and packaging waste collection.

This simply means reprocessing used material into a new product. Through various mechanical processes (sorting) in industrial composting plants, correctly separated bioplastics can be reused for new products (remelting or granulation). This upcycle process is what’s needed to transform linear supply chains into circular supply chains.

Secondly, biobased plastics can be collected and composted through biowaste collection.

After processing (organic recycling), the biowaste can be used either directly as compost or for biogas plants as renewable energy.

Processing involves heating the bioplastic to a high enough temperature that allows microbes to break it down.

Without that intense heat, bioplastics won’t degrade on their own in a meaningful time-frame, either in landfills or even your home compost heap.

So, should you use it?

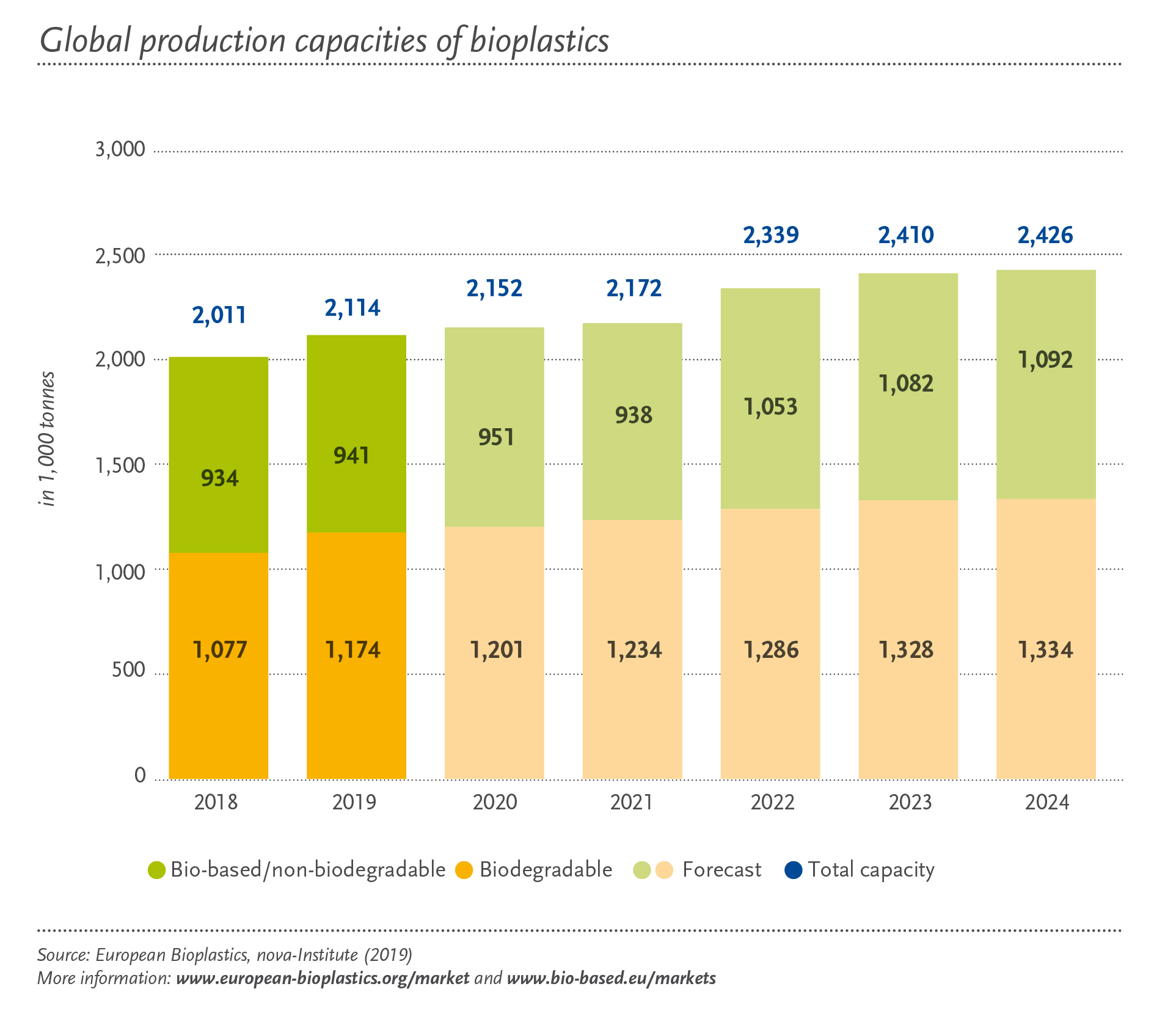

Consumer interest in sustainable alternatives to plastics are driving the growth of bioplastic.

Today, there are about 300 different kinds of bioplastics.

Bio-based plastics have benefits, including producing significantly fewer greenhouse gas emissions than traditional plastics.

However, this isn’t the end story.

Environmentalists still suggest that even if a widespread adoption of bioplastics may occur, it will do little to curb the amount of plastic entering waterways.

Most bioplastics need high temperatures to break down, and without adequate composting infrastructure and the capacity to collect green waste separately, they may end up in landfills where, deprived of oxygen, they may release harmful toxic chemicals to the environment.

To put it plainly, bioplastic products can end up being another example of greenwashing, a misleading marketing tactic on how sustainable a product truly is.

Promising examples of bioplastic

British product designer Lucy Hughes won the UK 2019 James Dyson Award for developing a bioplastic from fish waste that could possibly replace non-biodegradable, single-use plastics.

This fish scales and fish skin waste known as MarinaTex bioplastic can break down in four to six weeks when the soil is at the right temperature, which is faster than many other biodegradables.

The material itself is translucent and flexible, strong, has higher tensile strength and also economical (Atlantic cod could generate enough organic waste to produce 1,400 bags of MarinaTex).

Scientists from the University of Bath’s Centre for Sustainable Chemical Technologies (CSCT) in England are making polycarbonate from sugars and carbon dioxide to use in the manufacturing of drinking bottles, lenses for glasses as well as scratch-resistant coatings for phones, CDs and DVDs.

The convectional process for making polycarbonate involves the use of BPA (banned from use in baby bottles) and highly toxic phosgene. Bath scientists have discovered a cheaper and safer alternative to do it by adding carbon dioxide to the sugar at low pressure and room temperature.

The resulting BPA-free plastic is strong, transparent, scratch-resistant and bio-compatible: meaning it can be utilised for medical implants or as scaffolds for growing tissues or organs for transplant. Most importantly, it can be degraded back into carbon dioxide and sugar using enzymes from soil bacteria.

Conclusion

The use of conventional plastic to package consumer goods has reached an unprecedented level. Does this make the reinvention of plastic into bioplastics a solution to saving the planet’s natural system?

Bioplastic. Biodegradable. Biobased. Compostable. These terms get thrown around interchangeably quite a bit, but they don’t mean the same thing. The language and metrics have left so many consumers and those in the packaging industry confused.

And because of this confusion, the possibility exists for unscrupulous brands to market packages as “green,” “sustainable,” “natural,” or “biodegradable” when they are not and mislead consumers.

Bioplastic, of course, are often less damaging than the status quo, but they aren’t all created equal and aren’t entirely biodegradable. So as much as they are a good starting point, it’s still crucial to consider the material’s life cycle and assess its environmental impact.